BEACONSFIELD GALLERY, LONDON 29.11.10

I’m standing under a brick railway arch in Vauxhall. It’s the Arch Gallery, one of three spaces converted by the Beaconsfield Gallery out of what was once the London Ragged School ( said to be the school the film star Charlie Chaplin once attended – he certainly lived close by). On the wall of the gallery at the far end a video is projected which is exciting enough, but the music fills the space and travels up from the floor through my feet and fills me too. I can hear a tangy sound, like an anvil - metal, heat, energy. The experience is beautiful, inexplicable, visceral.

I’m watching young people dancing in a disco – or are they fleeing? And what about the colours drenching the screen? I am innocent of any technological knowledge so I’m free to imagine. The image comes to mind of the artist using a scalpel to slice the original colours into their constituent parts. You know as a child that when you mix blue and yellow you make green and that’s that – no going back. But Dean has conjured up hues by parsing and mixing and then brushing them on with the fluidity of water colours.

But what is the video about, I ask? I must have slept through 1984 because The Terminator passed me by. Fortunately I have my two daughters beside me. I gather that someone or something marches through a jolly disco and he or it is not full of the good intentions one would hope from a stranger. What I didn’t see – but my daughters point out – is that the way the colours change have technological overtones such as infra red vision and thermal mapping. And are those skeletons you can almost see through the flesh as it is stripped away in fleeting moments? We walk a few hundred yards back to my daughter’s house and within a couple of minutes my son-in-law gets up on his screen a Hungarian clip of the film. From my daughter’s description he pin points the exact tiny fragment (1.75 seconds) Dean uses on a continuous loop.

Like Christian Marclay Dean appropriates film clips and re mixes sound, but he also, as they say, ‘takes up a position behind the camera’. This work is called Christian Disco/Terminator. He was recently ordained in the Church of England, and the breadth of his experience shows in the way he refers in his conversation to two charismatic Christians as diverse as Martin Israel and Gladys Aylward (one an Anglican priest the other a lay woman) signals someone to be heard. He says he focuses ‘on the most fundamental aspects of the human condition...I am interested in the relation of contemporary art and religion, but do not recognise any shared language with which to discuss this – at least, not at the level that either discipline requires. I might be wrong, of course. In any case, my work is driven by this question.’

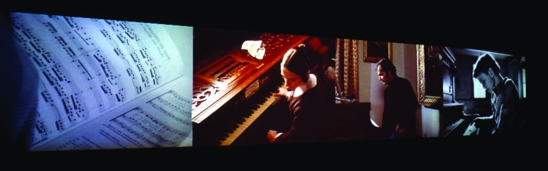

The exhibition offers visitors the opportunity to view the range of Mark Dean’s art works made over the past twenty years. This includes Experimental Religion – an audio recording of Gladys Aylward preaching mixed with Ingrid Bergman playing Aylward in a Hollywood biopic and How Can You Mend a Broken Heart linked with 1 Corinthians chapter 11 verses 23-26. There’s even a tempting still of the head and shoulders of Sid Vicious with his eyes shut entitled Open Your Eyes. What is there to resist?

Mark Dean’s exhibition The Beginning of the End will run until February 13.

http://www.tailbiter.com

http://www.beaconsfield.ltd.uk